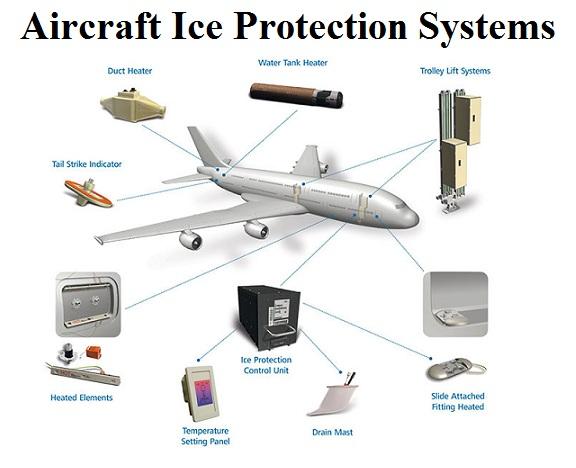

Aircraft Ice Protection Systems

Description

Aircraft and engine ice protection systems are generally of two designs: either they remove ice after it has formed, or they prevent it from forming. The former type of system is referred to as a de-icing system and the latter as an anti-icing system.

De-Icing Systems

A de-icing system has two very attractive attributes. First, it can utilize a variety of means to transfer the energy used to remove the ice. This allows the consideration of mechanical (principally pneumatic), electrical and thermal methods.

The second attribute is that it is energy efficient, requiring energy only periodically when ice is being removed, with some mechanical designs requiring relatively little energy overall. This is a significant consideration when designing ice protection for aircraft with limited excess power.

The principal drawback to the de-icing system is that, by default, the aircraft will operate with ice accretions for the majority of the time in icing conditions. The only time it will be free of ice accretions will be the time during and immediately after the cycling of the de-ice system.

This requires an understanding on the part of the designer and the pilot of what effects the ice accretions will have on aircraft performance, both prior to and during system operation.

Any design which utilizes either a mechanical means of breaking the bond of ice to the surface, or which operates on a periodic cycle, is necessarily a de-ice system.

Anti-Icing Systems

Anti-icing systems reverse this paradigm. Properly used, they prevent the formation of ice continuously, resulting in a clean wing with no aerodynamic penalties. An anti-icing system must have a means of continuously delivering energy or chemical flow to a surface in order to prevent the bonding of ice.

The typical thermal anti-icing system does this at significant energy expense. The concept is not viable for aircraft that do not have the requisite excess energy available during all flight phases. An exception to this is the use of a chemical system such as TKS.

Design Considerations

It is not uncommon for a system that is designed as an anti-ice system to be used initially as a de-ice system. For example, the manufacturer may recommend that the wing thermal ice protection system be selected on when ice accretion has been detected, thus initially bypassing the anti-ice capability.

Once selected on, the system is usually left on until icing conditions have been departed, allowing the anti-icing capability to function as intended.

The selection of system design and the determination of operating procedures are based on the manufacturer’s understanding of the tolerance to ice accretion exhibited by the particular aerodynamic surface.

For example, turbojet/turbofan engine inlets are almost universally protected by thermal anti-icing systems. These systems are nearly always used in an anti-icing manner, which is to say they are selected ON upon encountering visible moisture and crossing below a temperature threshold.

This approach is due to the intolerance of the compressor inlet to ice ingestion; an imprecise de-ice cycle would lead to damage and/or loss of power.

On the other hand, the same airplane may use a thermal anti-ice system for the protection of the wings, but the manufacturer may recommend that the system not be activated until ice accretion is noted on some representative surface.

The judgment here is that the aerodynamic penalties associated with such “pre-activation” ice are acceptable and pose no safety hazard.

Any time a design utilizes an ice detection system as a primary and automatic means of operating the ice protection system, the system becomes a de-ice system. An automatic means of activation will necessarily have a threshold for triggering both activation of the system and de-activation of the system.

This is almost universally accomplished by means of an ice detector, which, as the name implies, must have some ice present to detect. Thus, the system is not activated until ice has accreted. Once the ice has been removed, the system automatically terminates, and awaits another ice detection trigger before cycling again. This is the de-ice cycle.

Thermal Systems

A thermal anti-ice system is designed to operate in one of two ways: fully evaporative or running wet. In the former case, sufficient energy is provided to cause impinging super cooled water to completely evaporate.

This has an obvious advantage of protecting the aft, unheated portion of the airfoil, since the evaporated water cannot re-condense before the airfoil has passed. It is a very effective means of ice protection, but the concept requires a great deal of excess energy.

A running wet system can only prevent impinging water from freezing. This requires rather less energy. However, it can fail to prevent runback ice, which forms when the running water passes aft of the heated surface and freezes.

Any fully evaporative system will necessarily transition through a running wet phase as it both heats and cools. The ideal method for operating a fully evaporative system is to activate it prior to entering icing conditions, thus allowing the surface to stabilize at the required temperature.

Many contemporary designs feature a minimum engine rotor speed that is automatically limited when ice protection is selected on. This ensures adequate heat to the surfaces, but may also impact descent planning.

A thermal de-icing system requires much less energy. Using either engine bleed air, exhaust-heated air, or electrical heating, this system is intended only to periodically break the bond between accreted ice and the surface. A typical example would be propeller de-ice systems, which use electrically heated pads on the inboard leading edges of the propeller blades.

Pneumatic De-Ice Boots

A very common de-icing system utilizes pneumatically inflated rubber boots on the leading edges of airfoil surfaces. This typically includes the wings and horizontal stabilizer, but may also include struts, cargo pods, or even antennae. The system uses relatively low pressure air to rapidly inflate and deflate the boot.

This is usually done in a sequence of segments, for example, the outer wings followed by the inner wings followed by the horizontal stabilizer.

Depending on the manufacturer’s specifications, the system may be operated either automatically, through a timing circuit, or manually, using a cockpit control to initiate the boot cycle sequence.

Early pneumatic boot designs had relatively low volume air supplies to draw from, and were slower to inflate and deflate.

A phenomenon which was thought to be occasionally observed with these systems was known as “ice bridging”, in which the boot expanded under the ice and stretched it without breaking its structure.

This led to a space beneath the ice shape which allowed the boot to inflate and deflate with no effect. The problem was addressed by allowing a particular thickness of ice to develop before inflating the boot. Once the requisite thickness was attained, the boot inflation would shatter the ice and clear it off the surface.

At least with contemporary, rapidly inflating systems, there is almost no evidence other than anecdotal which supports the existence of this phenomenon. That said, research dating from the mid 1950’s and validated within the last few years has indicated that several uniform cycles of boot inflation/deflation may be required to thoroughly shed an ice accretion.

It is likely that the results observed after the first couple of cycles may be less than satisfactory. It becomes extremely important to adhere to the manufacturer’s recommendations for system operation as found in the relevant Pilot Operating Handbook or Flight Crew Operating Manual (or their equivalents).

Equally important is the correct maintenance of the boots, including adequate treatment with restorative substances and inspection for pinholes and other damage.

Write a Comment